December 2011

Arnault of Zwolle's lute design;

a puzzle solved?

Arnault of Zwolle was a monastically trained late mediaeval writer and scholar who left us a very interesting set of instructions on how to design and make various musical instruments in a manuscript dating from around 1440. It is thought his name refers to Zwolle, a town in Holland, to the north east of Amsterdam; he was employed as a doctor and astronomer/astrologer by Philip the Good and wrote his MS in Dijon round about 1440, when Arnault was employed as physician and astronomer for Phillip The Good, Duke of Burgundy. Between 1453 and 1461 he moved to Paris to work for Charles VII and later Louis XI. Arnault died of the plague in 1466.. There is a thorough discussion of his drawing of a lute and its mould, and a translation of his latin text in a paper by Ian Harwood in the Lute Society Journal (1960). But the curious thing is that the lute he describes and shows in detail is really rather unlike many of the lutes that we see in paintings. (No lutes at all have survived from this period so we are firmly in the realms of art history as far as the mediaeval lute is concerned.) There are a fair number of paintings and manuscript illuminations to document the design (or rather range of designs) of the mediaeval lute. Among the earliest pictures of a European lute is found in the Cantigas de Santa Maria, a book commissioned by Alfonso the Wise around 1250. (There is another image of a lute included in a book of chess problems also commissioned by Alfonso in 1283.) Both illustrations show a lute with a large body, a very wide string spacing at the bridge, converging to narrow string spacing on the fingerboard and a smooth curve between the neck and the body. It is in essence a mediaeval Arabic 'ud. The Cantigas shows a rather oriental-looking pegbox whereas the chess picture looks more like the pegboxes we are used to seeing on existing lutes.

Cantigas de Santa Maria c.1255. codex T.I. 1, Library of El Escorial, Madrid

The Book of Chess, Dice and Board Games, 1283. St. Lorenze del Escorial, Madrid

By about 1300 a similar instrument is shown in the first representation of a lute in England. The Steeple Aston cope, a beautiful embroidery in the so-called opus anglicanum technique, shows an angel on horseback playing a lute with a similar shaped body and string band to that in the Cantigas de Santa Maria (though the pegbox is more like that in the chess book) the neck still flows in a smooth curve into the body. I have argued in an earlier talk that this design may indicate a construction where the neck and neckblock are carved out of one piece of wood with the ribs glued into a rebate.

Steeple Aston Cope c.1310-1340. V&A Museum, London

A similar design with a wide spacing at the bridge and a smooth curve at the shoulders is shown in the bas relief carving of a lute by Andrea Pisano dating from around 1340 in the campanile in Florence.

Andrea Pisano (c.1290-1348) Orpheus as luteplayer. campanile, Florence c.1340

In fact by this time, around 1340, similar lutes or 'uds were to be found all over Europe: the Wenceslas IV bible, (Bohemia c. 1340) shows essentially the same design, played with a huge plectrum. It has a small rose and a deep back made with broad ribs (which we can see clearly for once), and shoulders so sloped that there seems little distinction between neck and body.

Wenceslas IV bible, (Bohemia c. 1387 - 1400) Vienna Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek MS 2759/64, fol. 81

We move from the sacred to the secular with a slightly later image found in an illumination depicting the garden of love (in the tradition of the Roman de la Rose) in one of the Harleian manuscripts in the British Library. The figure of Idleness (meaning leisure time, rather than in its more perjorative sense) gives you the key to enter the enclosed garden. The lute is very similar to the earlier examples.

Romance of the Rose, British Library MS Harl 4425 fol. 12v

A more risqué version of the garden of love, again showing a similar lute is found in

De Sphaera, Venus, Garden of Delights, attr. Cristoforo de Predis c.1470 . Biblioteca Estense, Modena MS. Lat. 209, X. 2. 14

An illustration to Bocaccio's Lives of Famous Women showing women practising various trades (in this case, that of instrument maker welcoming her customers) shows a gittern and a lute hanging on the wall (this pairing is surprisingly common in mediaeval art, perhaps reflecting contemporary duet playing practice)

Boccaccio, Des clares et nobles femmes (French after 1401)

All the lutes in the pictures so far look very similar, with smoothly sloping shoulders curving into a narrow neck, and the rose well down the soundboard. However not all mediaeval lutes were in this style; here is a painting by Gaddi from about 1370 showing a 4 course lute with a well defined angle between neck and body. In fact it is a remarkably modern looking lute, not a bit like the Arnault design, more like the surviving lutes of the 1520s onward, - in fact all surviving lutes - which is why the curved neck/body design has not in the recent past received the attention I believe it deserves.

Agnolo Gaddi, The Coronation of the Virgin, probably c. 1370. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. n.314 Samuel H. Kress Collection 1939.1.203

Probably the closest match I have found to Arnault's lute drawing is in another portrayal of a lute with a hard neck joint angle and an unusually long neck in a 15th century source . Though we cannot be sure of the accuracy of the depiction here, given the rather approximate draftsmanship of the picture, it still is not very close to the peculiar Arnault shape.

Valerius Maximus, De factis dictisque memorabilis. (French 15th cent.) Biblioth¸que National, Paris

Then, specially for Thomas Schall, Frankfurt's famous son Isreal Meckenem showing a version of domestic harmony c. 1440-1500 Notice the beautiful lute case lying half open.

Isreal van Meckenem c. 1440-1503

And another version of domestic harmony by Meckenem with a fine chained monkey, which must indicate a wealthy middle class merchant or equivalent.

Isreal van Meckenem c. 1440-1503

To return to the flowing 'Ud-derived shape for a moment, a 14th century Italian illustration to Boethius, De arithmetica, has an image of music and her attendants, one of them playing a very large lute. No doubt this reflects the mediaeval interest in the relationship between music and number; mediaeval thought, dividing up the seven liberal arts, grouped music in the quadrivium, alongside arithmetic, geometry and astronomy, contrasting with the 'lower' arts of the trivium, or threefold path to eloquence: grammar, logic and rhetoric.

Boethius, De Arithmetica, Music and her attendants, Italian 14th cent, Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale MS VA 14

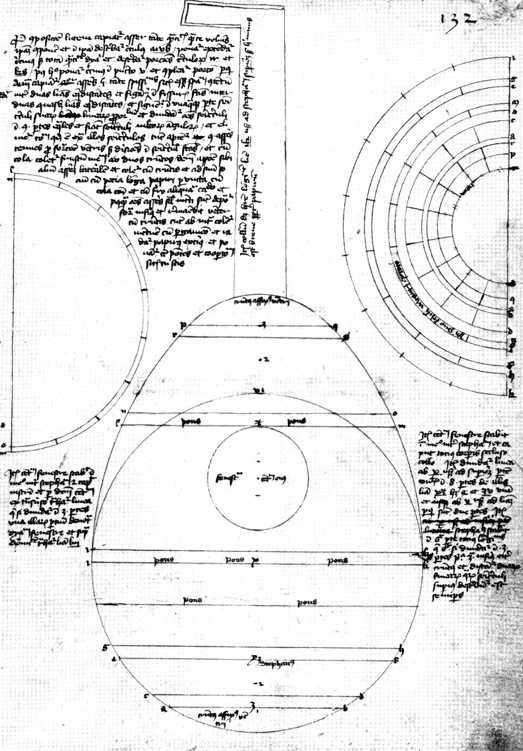

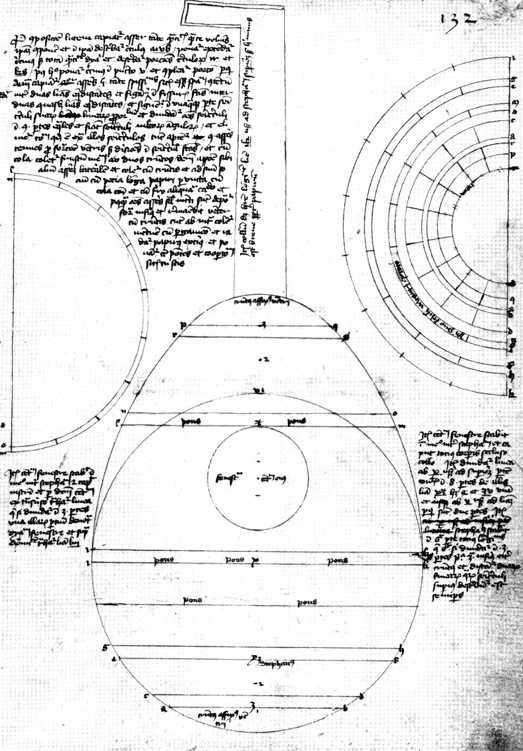

Which leads us back to Arnault of Zwolle who was himself interested in geometry. He worked as physician, astronomer and astrologer to Philip the Good. The clavicembalum which he shows in his manuscript is, like the lute, based on geometrical principles. I think he may have been at least as interested in setting forth the underlying geometrical basis of things as in recording physical details. In this he would have been rather typical of many mediaeval thinkers, although part of the drawing does show how to make a lute mould and the latin text briefly describes how to construct the lute. Here is his drawing. It has a sharply angled neck joint - as we have now seen, lutes with both hard neck joints and with smoothly flowing joints co-existed at the time though the curved joints predominate before his time. The neck is quite long - he says in the accompanying notes that he has cut the neck short because his parchment is not big enough to show its full length. So far so good. But note the very strange curve of the body as it approaches the neck - something I have never seen in any picture. The body suddenly turns in more sharply just before it arrives at the neck joint. The resulting joint between neck and body is more or less a right-angle.

Arnault builds up his geometrical lute design as follows. First, you draw a circle with a diameter of the width of the lute you want. Then, centred on the two ends of the diameter of the circle to right and left, you draw two arcs, whose radii are the same as the diameter of the circle. By some means, which Arnault does not specify, you define the centreline of the lute, and, using the point where this crosses the circle as another centre, you draw a second smaller circle whose circumference is tangential to the large arcs on either side. This produces the curious change in angle as the body curves in towards the neck. (Some of you will recognise this as the same geometric construction as the three-centred arch which, maybe not coincidentally, was then becoming fashionable in contemporary French architecture.) I have drawn in the lines which are radial to the centres of both the large arcs and the small circle and which define the change-over point of the two curves. Finally you then add the neck, the length of which is the same as the diameter of the circle you started with.

This gives eleven and a half fret spaces on the neck - very long, and unusual for the period, though as we have seen, there is at least one manuscript illumination showing a lute with a very long neck. (Some later lute designs did use a version of this kind of geometry to produce a body which had a slight increase in inward curvature towards the neck - but never as extreme as this, and not at this early period.) As you can see, the result looks remarkably UNLIKE the vast majority of the lutes we have seen.

Why should he have used this second circle? Just adding the neck to the shape produced by the long arcs and the first circle would have produced a lute perfectly in accordance with the then current sharp angled lutes we have seen in contemporary paintings such as the Gaddi.

I would like to propose a solution to this puzzle. Arnault was not himself a lute maker, and if we picture him closely questioning instrument makers, but then misunderstanding or misremembering what he had been told by the time he got back to his study, I suggest that he had been told that the transition between neck and body involved the use of another circle and drew it in the wrong place, thus producing an inaccurate version of the OTHER lute type. But, being more interested in geometry, and especially the currently fashionable three-centred arch geometry, he ignored, or did not care about, the discrepancy.

However we can redraw his diagram using the same two circles to match exactly the lute designs that we do see in the paintings. We begin with Arnault's circle, two arcs and midline.........

But now we take his next small circle and draw it OUTSIDE instead of inside the large arcs

This produces curves around the neck joint exactly as we see them in numerous paintings. This also has the effect of making the body longer and the neck shorter, much more like the majority of the paintings.

For instance this Florentine sculpture of a 5 course lute from around 1426, just a few years before the putative date of Arnault's treatise.

Luca della Robbia, Cantoria [detail] Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

Also from 1426, a painting by Masaccio now in the National Gallery. Note the curves between neck and body. On the other side of the throne there is another angel playing a similar lute. These are semi-multiribbed lutes, with five courses -These are the earliest dateable representations of five-course lutes that I know of.

Masaccio, Virgin & Child 1426, National Gallery, London

And another painting by Sassetta in the Louvre.

20

20

Stephano di Giovanni (Sassetta)(c. 1392 - 1450) Virgin & Child c. 1400. Louvre, Paris

And another image from a triptych by Goswijn van der Weyden now in Burgos Cathedral, Spain, c.1440, almost exactly the date of Arnault's drawing.

Another pairing of lute and gittern occurs in this altapiece by Pera Sera. The lute is a classic of the type and could be the model for my revised version of Arnault (apart from the second rose).

Pere Sera, Virgin and Child 14th cent altarpiece for the church of St. Clara, Tortosa. Museo de Arte Cataluna, Barcelona

Then there is a famous fresco in Ferrara of around 1490, wonderful for lute makers as it shows the front and back of what seems to be the same instrument (good enough to build from!). You can see how the lute ribs curve into, and then become lost in a rebate in the neck. It is just feasible that such lutes were carved from the solid, as some people have suggested, but for me this seems utterly unlikely, if only because of the detail of the endclasp which implies a built-up construction, and would be completely irrelevant to a carved body.

Francesca della Cossa, Spring, Fresco c. 1490, Schivanoia Palace, Ferrara

Moving on to the start of the 16th century, and the earliest period from which we have surviving lutes, the curved neck joint still persists in use. Fascinatingly both types of lute appear in the same painting of the Last Judgement by Bosch. None of Bosch's paintings are dated, but this is likely to be c. 1500. One devil is playing a curved joint lute while another devil seems more up to date, with a lute of the type which would later come to dominate, to the total exclusion of the more curvilinear form.

Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450 - 1516) The Last Judgement [detail] c. 1500, Akademie, Vienna

Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450 - 1516) The Last Judgement [detail] c. 1500, Akademie, Vienna

As an aside there is a little-known page of drawings by Bosch of cripples and beggars with lutes. Whether this is a work of social realism, symbolism, absurdism, or satire (and if so, against whom) I leave you to speculate. The images include someone playing a pair of bellows as if they were a lute - something you see in quite commonly in Flemish "low-life" pictures. All the lutes are modern-looking renaissance instruments.

Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450 - 1516) Page of drawings [detail], Albertina, Vienna

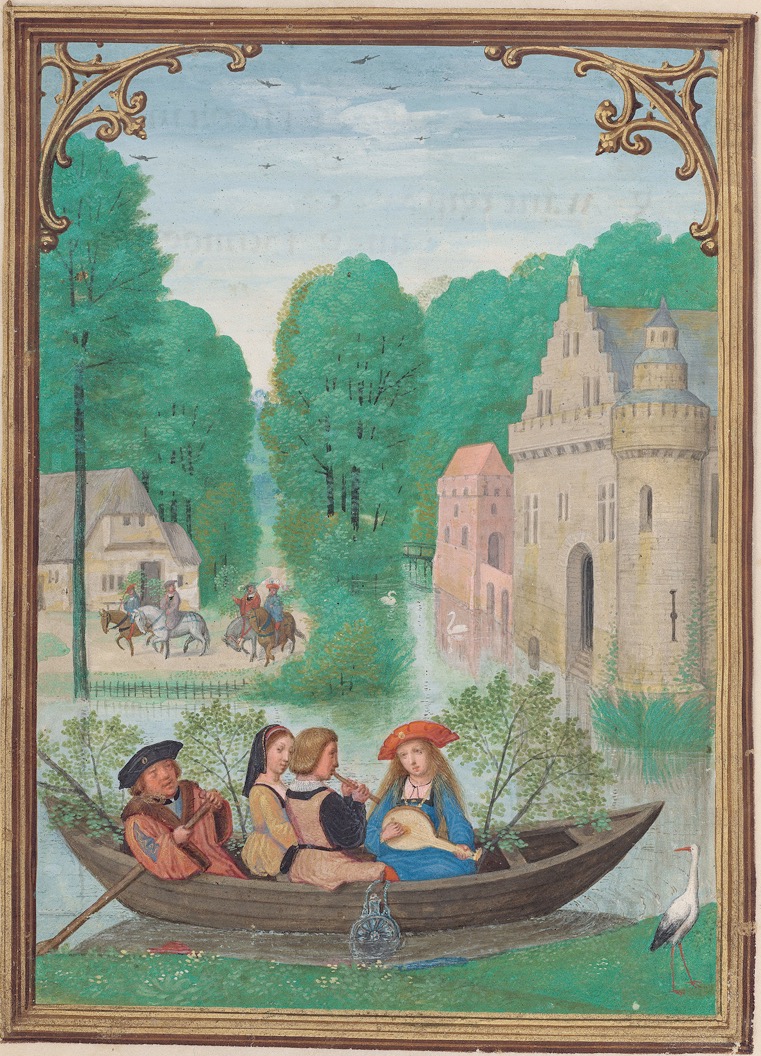

I would like to end with two more images from around 1500 which encapsulate the puzzle as I see it. First, a lute with a neck almost as long as Arnault describes and with the hard angled neck joint, but without his characteristic and I think improbable body shape. This is found in an illuminated book of hours - these were produced in very large quantities in the Netherlands, almost mass-produced, around 1500, and many copies were exported to England. The image, depicting one of the spring months, shows ladies and gentleman in a boat on a castle moat. A bottle of wine is cooling in the water.

(Flemish, c. 1540) New York, The Pierpont Morgan Library, MS M399, fol. 6v

Second, a lute such as I suggest Arnault might have intended to design, appears in a detail of a painting c. 1500 by Jan Mostaert in the Liverpool Art Gallery. I suspect the dying hollow tree represents the Old Law of Moses, and the young tree represents the New Law of Christ, though it is the lute which concerns us here - and it is the older dying form he shows, though to suggest this also was part of the theology of the painting would probably be pushing it a bit!

Jan Mostaert (c. 1475 - c. 1555) Portrait of a Young Man [detail] Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Copyright David Van Edwards, Norwich, 2004