The word tiorba first appears in print, to my knowledge, in 1598, when John Florio included it in his Italian-English dictionary, A Worlde of Wordes. Some modern books quote its inclusion in the 1544 inventory of the Accademia Filarmonica, Verona, though I suspect Una tiorba was added at the end of the century. (Short of going to Verona and examining the manuscript I can see no way of resolving my doubts.) Certainly there seems to be no musical need for a tiorba until at least the mid-1570s, when the Camerata were experimenting with their nuove musiche. Mersenne (1637) says that it was invented in Florence 'thirty or forty years ago' by le Bardella,9 i.e. Antonio Naldi, whom Caccini also praised for his continuo realizations.10 From c.1600 the tiorba was considered synonymous with the chitarrone. It is named in printed music from 1600 until the 18th century. Solo music in tablature was printed by Meli in 1614, 1620; and by Castaldi in 1622. This latter book contains a portrait of Castaldi (Fig. 4) playing his tiorba, which is seen to be single-strung and to have a single rose in the soundboard, a possible distinction from the chitarrone also depicted by Praetorius (1620).

Figs 4, 5 & 6

Left: Bellerofonte Castaldi with his tiorba from his Capricci a Due Stromenti (Modena, 1622)P 28v

Centre: Tiorba (? or chitarrone) by Wendelio Venere (Padua, 1611) overall length 140cm; 4' 71/8”. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, no. SAM 43.

Right: Geronimo Valeriani, lutenist to the Duke of Modena by Lodovico Lana (l597-1646). Photo courtesy of Sotheby, Parkc Bernet & Co.

Fig 7

Detail from A Musical Company by Gysbert van der Kuyl (d. 1673,). Photo courtesy of Sotheby Parke Bernet & Co. (But note new attribution)

He added the correction that his engraving of a tuorbe (Fig. 16) should be called arciliuto, and that the tiorbe was larger and single-strung. Castaldi wrote duets for the tiorba to play with the tiorbino, tuned an octave higher; and in 1645 was printed the anonymous Conserto Vaga for 11-course tiorba, liuto and chitarrino. Both these works were written out in tablature.

Starting with the trio sonatas of Cazzati in 1656, the tiorba was used for the following thirty years as an alternative to the violone, reading from bass clef. The tiorba would play the bass and add harmony to that of the organo part. From the 1680s the arciliuto gradually replaced the tiorba, probably because the upper two courses, being at lute pitch, gave the arciliuto greater range for the bass, and allowed room for harmony above that bass. The tiorba was used on its own to accompany a solo voice in opera (Legrenzi, Eleocle, 1675)12 and church music. From 1614 St Mark's, Venice employed singers who doubled as theorbists,13 the last theorbist there dying in 1748.14 Schütz marked a section of Veni dilecte mi' in Symphoniae Sacrae (Venice, 1629) voce con la Tiorba, and Cavalli's Ave Maris Stella has a separate part for tiorba written out in Cavalli's autograph. As late as 1717 motets were printed with a part for violone ò Tiorba.15

Theorbo

The theorbo (or theorbo-lute: Mace used the terms interchangeably for the same instrument)16 is first referred to in John Florio's Italian-English dictionary A Worlde of Wordes (1598), when he translated Tiorba as " kind of musicall instrument used among countrie people'. Both that definition and that of the 1611 edition, ‘a musical instrument that blind men play upon called a Theorba', show that the instrument was unknown in England at that time. Dr Plume noted that Inigo Jones first brought the theorbo into England circa 1605.17 Angelo Notari came to England c. 1610 and published a book of songs con la tiorba in

London in 1613. He may well have introduced the theorbo. Michael Drayton (1613) implied that the theorbo was wire-strung.18 In The Maske of Flowers (1614) a song was 'sung to Lutes and Theorboes'.19

Fig 8

Detail from Mary Sidney, Lady Wroth, holding a theorbo (c. 1620) attributed to John dc Critz (1555-1641). Penshurst Place, Kent.

In the well-known portrait (c. l620) of Mary Sidney (Fig, 8) she is holding a 13-course single-strung theorbo closely rcsembling that illustrated by Praetorius. Walter Porter's Madrigales (1652) call for Theorbos', followed by Child's (1639) and Wilson's (1657) Psalms, A number of manuscript collections of songs with tablature for theorbo have also survived.20 In 1652 John Playford printed the first of his collections of Ayres 'to sing to the Theorbo'. Almost every song book until the end of the century called for the 'theorbo' or 'theorbo-lute’.21 Samuel Pepys the diarist played the theorbo, calling it interchangeably 'theorbo' or ‘lute'. On 9 October 1661 he wrote,'put my theorbo out to be mended'. On 25 October, saw my lute, which is now almost done, it being to have a new neck to it and to be made to double strings'. On 28 October, my Theorbo done ..., and costs me 26s. to the altering. But he now tells me it is as good a lute as any is in England, and is worth well £10. On the subject of value, theorbos cost about £15 right through the l7th Century.22 Pepys wrote on 15 November 1667, 'we did play, he [Pelham Humfrey, lately returned from France] on the theorbo, Mr Caesar on his French lute, and I on the viol, but made but mean musique, nor do I see that this Frenchman' do so much wonders on the theorbo'.

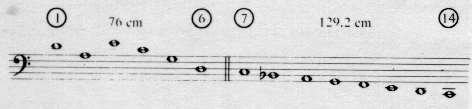

Thomas Mace (1676) gave instructions for playing solo and continuo on a theorbo tuned thus:

At least 7 courses were on the fingerboard. He added that some players lower the second course an octave if the theorbo is very large, and that smaller theorbos should be tuned a tone higher, in A.23

Fig 9

The theorbo half ofThe Lute Dyphone. T. Mace, Musick's Monument (London. 1676) p 32.

His engraving (Fig. 9) of The Lute Dyphone shows the distinctive pegbox peculiar to some English theorbos, which allowed basses to increase in length as they lowered in pitch. I know of no surviving instrument of this type, but see Lady with a theorbo (Frontispiece) painted by J. M. Wright c.1680. This theorbo seems to have 11 courses, of which 4 are unstopped. All are double, except the first. James Talbot (c. 1700) gave this tuning for an 'English Double Theorboe':

and this tuning for an 'English Single Theorboe':

He said both could have either 9 or 10 frets on the neck, and gave many variants of octave or unison double-stringing.24

Returning to music for the theorbo, about 1650 John Wilson wrote out solos in every key for a 12 course instrument with only the first course tuned to the lower octave. Of the tablature song accompaniments in the same manuscript, 36 indicate a theorbo tuned in G, and only 5 in A.25 Perhaps Henry Lawes was referring to the outlandish keys of the solos when he wrote:

That thou hast gone, in Musick, unknown wayes,

Hast cut a path where there was none before,

Like Magellan traced an unknown shore.26

Thomas Mace printed a long Fancy-Praelude, or Voluntary; Sufficient Alone to make a Good Hand, Fit for All manner of Play, or Use. About the mid 1680s the theorbo was gradually replaced for song accompaniment by the harpsichord, probably because it could not cope as well with the new melodic importance given to the bass by composers like Purcell. The advertisement which appeared in the Flying Post of 8 February 1701--J. Hare offers for sale 'a large Consort Theorbo Lute"27 ---was perhaps indicative of the disuse into which the theorbo had fallen. However, in 1707 Walsh printed A Complete Method for ... Thorough Bass upon ... Thaorbo-Lute, by ... Godfrey Keller, though in a later edition 'Theorbo-Lute’ was replaced by 'Arch Lute'. In the same year Francesco Conti played 'upon his Great Theorbo' in London.28 Handel wrote parts for teorba or theorba in his London productions of Giulio Cesare (1724), Partenope (1730), Esther (1752), and Saul (1739).

One silent musical use of the theorbo was recorded in the Burvell Lute Tutor (c.1660-72): ‘in a Consort one beates it [time] with the motion of the necke of the Theorbo, and every one must have the eye upon it and follow in playing his motion and keepe the same time with the other players’.29

Théorbe

The théorbe (tuorbe) was probably introduced into France c.1650 by Nicholas Hautman (Fig. 11), who died in 1663.30

Fig 11

Nicolas Hautman (d. 1663), engraving by Samuel Bernard (1615-87).

There is mention of its use in Mauduit's concerts of c. 1610,31 but then nothing until Mersenne (1637). Presumably the théorbe was rare in France at that time because Mersenne's well-known picture (Fig. 16) is in fact of an arciliuto, as he took pains to point out later in the book. In the text he described the Tuorbe Pratiqué à Rome as having 14 courses singly strung in A, with the first two courses tuned down an octave. In 1647 Constantijn Huygens sent the manuscript of his Pathodia Sacra et Profana to Ballard the printer in Paris. The songs then had a tablature accompaniment for theorbo, but Ballard persuaded Huygens to replace this with a figured bass that could be used by keyboard players.32 Presumably there were few theorbists in France then. Part of his own theorbo can be seen in a portrait of Huygens dated 1627 (Fig. 12)

Fig 12

Detail of Constantijn Huygens (1627) by Thomas de Keyser (1596/7-1667). London, National Gallery, no. 212.

From 1660 a number of continuo tutors were printed.33 In 1668 B. de Bacilly had printed his Trois Livres d'airs with a figured bass 'pour le Theorbe'. Six important tablature manuscripts of solo music survive for théorbe.34 This solo music may have heen played on a smaller instrument than that used for continuo. Talbot gave details of two sizes of ‘French Theorbo’.35 First was the normal accompanying instrument, tuned as Mersenne's, to which were attached the names Crevecoeur and Dupre, who supplied Talbot with his information and instruments to measure. Unfortunately he gave no measurements for this theorbo, but we do know that in 1703 a 'Mr Dupre, Lute Master has set up a School ... [in LondonJ where he teaches to play ... the Theorbo in Consort', and there was benefit concert for him the following year.36 A 12 course instrument of this type is shown in Puget's painting of 1687 (see cover). Of the fingered courses the first is single, and six are double in unison. The five diapasons are doubled at the octave. The second of Talbot's instruments is called ‘lesser French Theorbo for Lessons' and he gave a tuning a 4th higher than that for playing thorough-bass:

He added that a ‘French Theorboe may have 10 Frets' and that Crevecoeur told him that the 'Fr. single [strungl Theorboe ... [isj Fitter for Thorough Bass than Arch Lute, its Trebles being neither below the voice nor Instrs in Consort, as Arch Lute'. I confess I can make little sense of this, since the archlute was tuned only one tone lower than the thorough-bass theorbo, and its first rwo courses were not lowered the octave, Perhaps Crevecoeur was recommending the lesser French theorbo (tuned in D) for continuo work, and Talbot failed to grasp the distinction. Or, more likely, he has muddled the reason for preferring the theorbo. In 1701 Sauveur gave the standard A tuning for a 14 course Theorbe, the first two courses down the octave, adding that pour les Pièces (solos) the theorbe should have 10 frets, but only 9 pour jouer la Basse continüe.37 On further reflection I think the instrument in Watteau's Charmes de la Vie, c.1719 (Early Music, April 1976, p. 166) is probably a théorbe pour les pièces. In 1716 De Visée printed many of his theorbe pieces en partition, dessus et Basse for harpsichord or violin and bass-viol, because he said so few could read tablature.38 In the same year Campion the theorbist called tablature pernicieuse in his Traité d'Accompagnement.39

It is likely that the théorbe was taken to Germany and Prague from France, along with the French lute, so the use of the théorbe in those countries will be considered here. Silvius Leopold Weiss, more famous for his playing of the solo French lute, also played an equivalent of the theorbo. He said in a letter from Dresden dated 1723 that he had accommodated one of his instruments for accompaniment in the orchestra and in church. This had the size, length, power and sonority of a theorbo but was tuned differently.40 Baron (1727) said that Weiss played thorough-bass exceptionally well on lute or tiorba, and that the Theorba of his day often employed die neue Lauten-Stimmung (D minor tuning) with double-strung fingered courses but single basses.41 Weiss, in the same letter, confirmed Mace's statement that the theorbo was played with right-hand nails. The tiorba was used in Vienna, Prague and Berlin during the 18th century.42 When giving his seating plan of an orchestra (1752), Quantz wrote that the theorbist should sit behind the second harpsichord, between two cellists.43 . Baron was the theorbist Quantz worked with in Berlin from 1741 to 1760.

As late as 1780 La Borde distinguished between the Théorbe de pieces and the Théorbe d'accompagnement. He wrote that the first was monté à la quarte (i.e. in D ?), and that the second was au ton naturel (in A?) and had a larger body; his théorbe had 14 strings, 6 fingered and 8 basses, and 10 frets.44