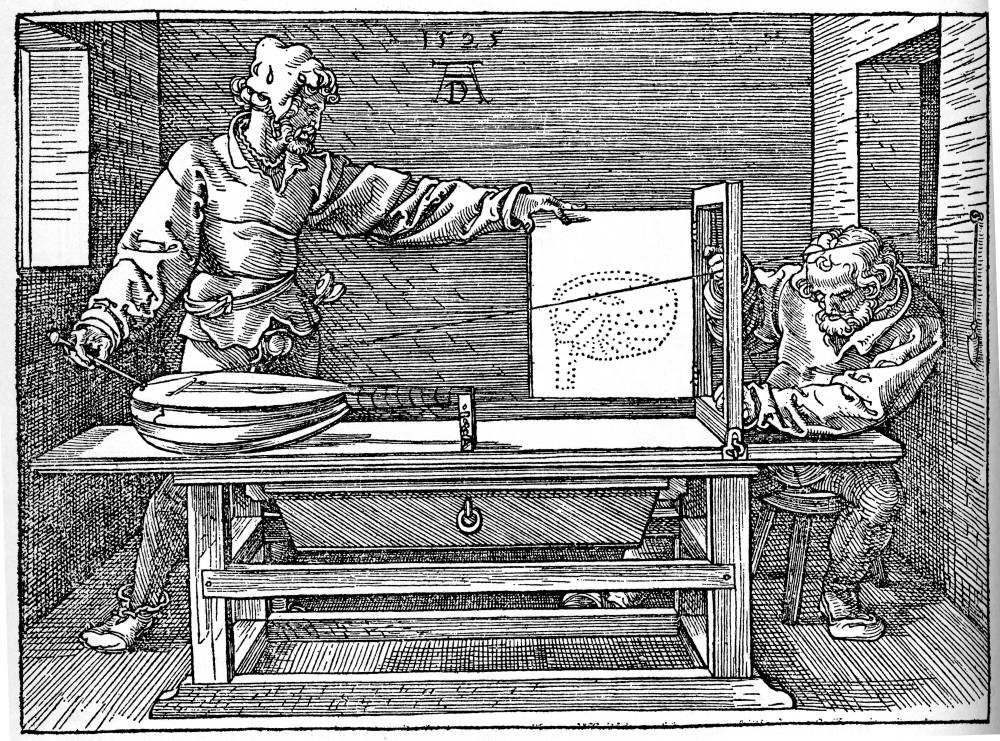

Dürer, Underweysung der Messung, Nürnberg 1525

|

Dürer published a book about the art of measurement in 1525 shortly before his death in 1528 and this illustration of a method of perspective drawing was the final image in the book.

And with this, dear gracious Sir, I shall end my writing, and by the grace of God I shall

In this wonderful device for painstakingly constructing a correct perspective, the imaginary eye is physically represented by the ring in the wall and the point where each part of the subject appears in the picture plane is measured from the taut string and then transferred to the picture as a dot. Dürer explains the procedure in detail:

Second Perspective Apparatus

If you are in a large chamber, hammer a large needle with a wide eye into the wall. It will denote the near point of sight. Then thread it with a strong thread, weighted with a piece of lead. Now place a table as far from the needle as you wish and place a vertical frame on it, parallel to the wall to which the needle is attached, but as high or low as you wish, and on whatever side you wish. This frame should have a door hinged to it which will served as your tablet for painting. Now nail two threads to the top and middle of the frame. These should be as long, respectively, as the frame’s width and length, and they should be left hanging. Next prepare a long iron pointer with a needle’s eye at its other end, and attach it to the long thread which leads through the needle that is attached to the wall. Hand this pointer to another person, while you attend to the threads which are attached to the frame. Now proceed as follows. Place a lute or another object to your liking as far from the frame as you wish, but so that it will not move while you are using it. Have your assistant then move the pointer from point to point on the lute, and as often as he rests in one place and stretches the long thread, move the two threads attached to the frame crosswise and in straight lines to confine the long thread. Then stick their ends with wax to the frame, and ask your assistant to relax the tension of the long thread. Next close the door of the frame and mark the spot where the threads cross the tablet. After this, open the door again and continue with another point, moving from point to point until the entire lute has been scanned and its points have been transferred to the tablet. Then connect all the points on the tablet and you will see the result. You can use this method for drawing other things.

Imagine how long this procedure would take! It must surely be an imaginary machine designed to make a theoretical point. Much as JS Bach’s Art of Fugue has been thought of as theoretical music it seems as if the great man wished to distil his knowledge in abstract form towards the end of his life.

The lute itself is a perfectly representative example of a sixteenth century lute. It could almost be a drawing of the six course Gerle lute which has survived and is currently in Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum, though this lute appears to have nine ribs whereas the Gerle has eleven. The end of the endclasp has the same design as several of the Laux Maler lutes. Notice too the deep neck, again like the Gerle, which has proved to be so comfortable for six course lutes, and suggests a style of holding with the left hand far removed from the twentieth century guitar style which used to be universally used until a few years ago. Eight tied frets on the neck and space for another; compare this with the Gerle which has the equivalent of 8.66 frets. A nice chunky little pegbox set at a right angle to the neck completes a very convincing portrait of the contemporary lute.

The date would be right for it to be a medium sized Laux Maler or Hans Frei lute, none of which have survived. It is hard to judge the comparative width of the lute, even though it is in a treatise on perspective, but maybe it is one of those small long form lutes which are so noticeable by their absence from museums and from pictures of the period, as I mentioned in my last Picture of the Month; but which we surmise must have existed. In this sense it is a pity it wasn't shown in plan view!

Interestingly this illustration describing one type of perspective was more or less copied by Salomon de Caus (1576-1626) in a book of instruction dedicated to Prince Henry, the son of Charles I, and based on lessons in perspective which de Caus gave to the young Prince.

It looks like a very dreary schematic lesson in a featureless, windowless room compared to Dürer’s drawing, notice how Dürer has included constructional details like the hinges and the catch holding the vertical frame as well as a stool to make the student comfortable and the much more interesting subject of a lute! Poor Prince Henry! (he died, aged 19, the same year this book was published)

A more practical method for actually producing a perspective drawing is shown just before our lute drawing. And Dürer rather caustically remarks: Solchs ist gut allen denen, die jemand wollen abconterfeien und die ihrer Sache nicht gewis sind “such is good for all those who want to make a portrait and who are not confident of their skill.”

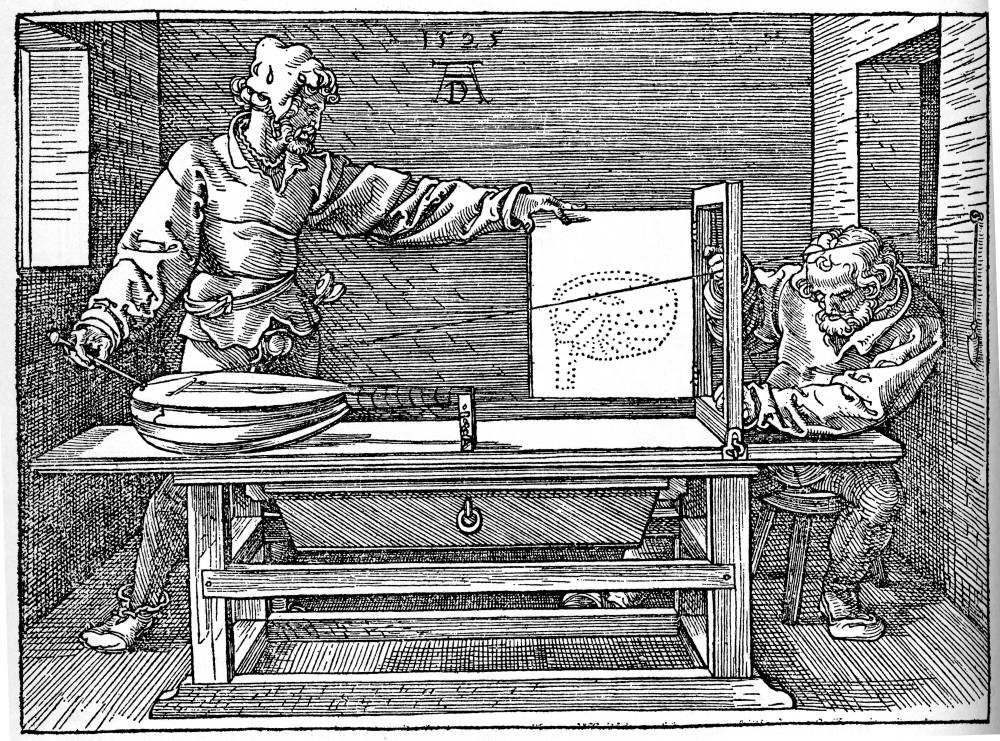

The more lively mind of Dürer is also shown in the second edition of the Underweysung which was published by Hieronymus Formschneider in 1538 after Dürer’s death in 1528. It included several more illustrations which were said on the titlepage of this edition to have been done by Dürer als er noch auf erden war “while he was still on earth” and which show two other devices for rendering perspective.

And especially this wonderful image of the jobbing artist confronted by abundant life! Dürer has a marvellous and little appreciated sense of humour. In the circumstances who could fail to be impressed with the phallic nature of the sight-vane and the fierce gaze of the artist, unconscious of the total effect?

|

|

If anyone has any comments about these pictures which differ from or expand

on mine, please do either email me direct or submit them to the lutenet at antispam/lute@cs.dartmouth.edu and I will add them to this page. Do please adjust this address by hand to remove antispam/ |

| Lutes | Bows | |

| History of the Lute | Build your own Baroque Lute | Build your own Renaissance Lute |

Copyright 1999-2012 by David Van Edwards