|

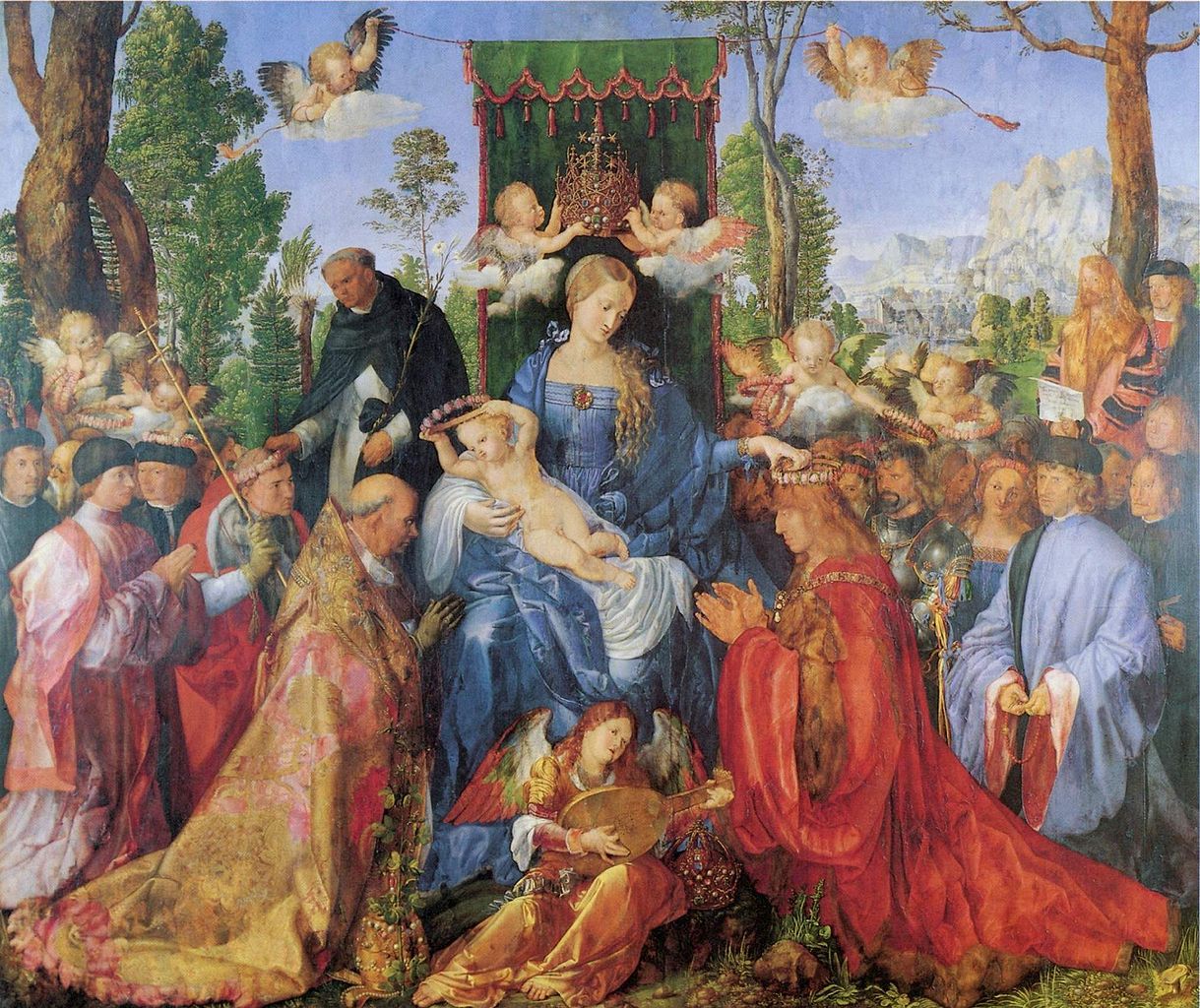

The main interest of this picture for us is frankly the circumstances of its commission rather than any detail of the lute itself or the playing position of its angelic musician. At present it is in a deplorable, but at least not restored to some bogusly unified, state of preservation and is in Prague museum, but it started life in glory as a magnificent altarpiece for the German colony's church, S. Bartolomeo, in Venice.

This church was shared between the two separate confraternities or clubs who ran the Fondaco dei Tedeschi,

This shows the Fondaco dei Tedeschi this year on the Grand Canal just to the left of the Rialto bridge with the spire of the church of S. Bartolomeo in the background.

This vast, dull and now rather run-down cross between a warehouse and a palazzo was the social and commercial centre of the German colony in Venice. One of its confraternities was run by the merchants from Nürnberg, the other by merchants from other parts of Germany, notably from Augsburg; and this latter fraternity was increasingly dominated by the important Fugger family. Dürer had stopped for a long time in Augsburg on his way, and when he finally arrived in Venice he stayed in a fine house lent by the Fuggers.

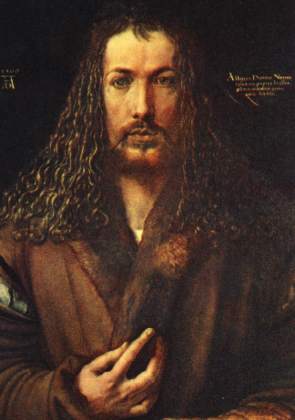

So it is perhaps not so surprising that Dürer, the citizen of Nürnberg, should have been commissioned by both fraternities, by the Germans as a whole, to paint this lavish altarpiece for “their” church. Because he also arrived as a world-renowned master, looked up to and copied by other artists; not the young beginner of his first visit eleven years earlier. He was treated like a celebrity and even warned not to eat at the houses of Italian painters lest he be poisoned! It looks indeed as if he was being used to showcase German art by the German colony. How else would he get away with the legend on the scroll he puts in the hands of his self-portrait to the right of the painting? "Exegit quinquemestri spatio Albertus Dürer Germanus MDVI" (Albrecht Dürer, a German, executed this in five months 1506)

The faces of all the participants are so vivid they have been assumed to be portraits of members of the German colony, but not many have been positively identified. The man next to Dürer has sometimes been claimed to be Fugger, but on no real evidence. The face at the bottom right of this detail is known however, he is Master Hieronymous, the architect of the new building of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi which replaced the one burnt down just a few years before. The Pope and the Emporer were not painted from life since Dürer had not yet met either, but were taken from portraits by other artists.

In many ways this is a deeply political picture. In its design and iconography it is clearly a Rosenkranzbild, a painting to celebrate the Brotherhood of the Rosary a confraternity founded in 1476 by the Dominican Jacob Sprenger. Designed to illustrate the idea of a universal brotherhood of Christianity, these showed clergy, led by the Pope, and laymen, led by the German Emporer, women and men, rich and poor giving or receiving garlands of red and white roses under an enthroned Madonna. Even though it is not certain that such a confraternity existed in Venice by 1506, it was all too convenient a symbolism for a German colony in Venice, struggling to maintain its independence from the conflict between the Pope and the Emporer, to show them both as united in harmony under the Madonna.

In the event a mere two years later in 1508 the two leaders did get together in the League of Cambrai, but it was not the sort of outcome that Venice wished to see! As Mary McCarthy wrote in her splendid book on Venice, Venice Observed, (Paris 1956) p.52

": ........ the reputation borne by the Venetians in the outside world. They had a name for sharp dealing, for "sticking together," artful diplomacy, business "push," and godless secularism -- traits familiarly ascribed to the Jews. anti-Semitism is often traced to a medieval hatred of capitalism. To the medieval mind, the Jew was the capitalist par excellence. But this could also be said of the Venetian, whose palace was his emporium and his warehouse.

Certainly the hatred excited by Venice during the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, the wave of revulsion that swept over Europe, culminating in the League of Cambrai of 1508, had an irrational, supercharged quality that was like modern anti-Semitism. The Venetians were more feared than they deserved to be. Boundless ambition was attributed to them; they were accused of seeking world-domination, which seems to have been far from their thoughts. Even Machiavelli was taken in by this myth, and the language of the pact of Cambrai, signed by most of the great powers of the Christian world, anticipates the Protocols of the Elders of Zion -- a case of mass hysteria being manipulated by a political adventurer, who, in this instance, was the Emperor Maximilian. Early in I509, abetted by the pope, this German prince issued a manifesto, in which he cited the Venetians as "conspiring the ruin of everyone," and he called on all peoples to partake in a just vengeance, to put out "like a common fire, the insatiable cupidity of the Venetians and their thirst for domination." It was Maximilian himself, as a matter of fact, "the last of the knights," as he was styled, who was plotting a universal kingdom, and who, shortly afterwards, had the notion of making himself pope. But Christendom agreed with him that Venice was the real enemy. He was joined by the king of France, the king of Spain, the king of Hungary, the duke of Milan, and the duke of Savoy. The pope, Julius II (friend of Raphael, Michelangelo, and Bramante), laid Venice under an interdict and proclaimed the war against her to be a holy crusade, in which all measures were justified.

The results were not as conclusive as might have been expected; the allies fell out among themselves, and Venice was only partly dismembered. Nevertheless, this holy war against her was a moral shock from which Venice did not recover. Her decline as a power dates from the Cambrai period. ................”

Venice Observed, Mary McCarthy p.52

Also, as we now know from the wonderful research of Sandro Pasqual and Roberto Regazzi into the lutemakers of Bologna, (Le radici del successo della liuteria a Bologna, Florenus Edizioni 1998) lute-making at this time was an enterprise on an almost industrial scale which could and did lead to riches and social standing in the German communities of these North Italian cities. Thus the lute playing angel is as likely to be a product placement for the specifically German nature of this craft and locally important industry, as it is to be the tribute to Giovanni Bellini which all the art historians claim.

The angel itself is playing a rounded, Venetian shaped, instrument in a seemingly entirely naturalistic way. However the position of the right hand fingers is rather odd, with the two middle fingers close together and apparently resting on the soundboard. I believe this has nothing to do with contemporary playing styles but everything to do with the iconography of the sacred. This hand position, with the joined middle fingers and spread apart outer fingers is symbolic to Dürer of profound and reverent prayerfulness. It crops up time and time again in praying Madonnas such as this in the Paumgartner Altarpiece, 1500:

and in the Christ child among the Doctors of later in 1506

And, most spectacularly and almost blasphemously in his self portrait of 1500 which shows Dürer in the pose of Christ, his hand in the Redeemer blessing position.

Thus we should see this lute-playing angel as a tribute to the sacred blessing of music, to political peacemaking, and to the secular commerce of the German colony, as well as a renaissance symbol of the harmony between people which is celebrated in the picture as a whole. Altogether a fitting focal point for a painting which celebrates the harmony between sacred and secular..

|