Structure of the Western lute.

The structure of the Western lute evolved gradually away from its ancestor the Arab lute or ‘Ud, though some features have remained sufficiently consistent to constitute defining characteristics. Chief among these are: a vaulted back, pear-shaped in outline and more or less semi-circular in cross-section, made up of a number of separate ribs; a neck and fingerboard tied with gut frets; a flat soundboard or belly in which is carved an ornate soundhole or ‘rose’; a bridge, to which the strings are attached, glued near the lower end of the soundboard; a pegbox with pegs inserted laterally; and strings of gut, usually arranged in paired courses.

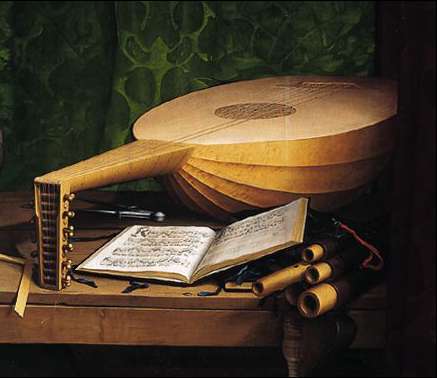

The Ambassadors (detail) Hans Holbein, National Gallery, London. (Nb. this shows a 16th century lute)

The ribs, of which the body is constructed, are thin (typically about 1.5mm) strips of wood, bent over a mould and glued together edge to edge to form a symmetrical shell. Although the overall sizes of lutes vary considerably, there is much less variation in the thicknesses of their constituent parts, and even very large lutes have ribs of less than 2mm. The glue joints between the ribs are reinforced inside with narrow strips of paper or parchment. Many surviving lutes also have five or six strips of, usually, parchment glued round inside the bowl across the line of the ribs. The number of ribs varies according to date and style from only seven to more than 51, but it is always an odd number because lute backs are built outwards from a single central rib. Many kinds of wood, even sometimes ivory, have been used for the back. Maple (acer spp. ) and yew were the favoured local European woods but exotic woods from South America and the Far East such as rosewood, kingwood and ebony, were used as they became available in the 16th century. The extent of their use by 1566 is revealed in the inventory of Raymond Fugger (see Smith, 1980) In these cases the end of the neck itself, suitably rebated, may have formed the block to which the ribs were glued. However even by 1360 there are already some pictures showing lutes with a sharp angle between neck and body, implying that the separate block, which is universally present in surviving lutes, was not unknown. The overlap of these two forms lasted at least two hundred years. For instance, The Last Judgement by Bosch c.1500 (Vienna Academy) still shows both forms in one picture. In the later two-part construction the joint is a simple glued butt joint, secured with one or more nails driven through the block into the end-grain of the neck. This simple joint proved adequate for the rest of the lute’s history Later still, a protective outer reinforcing strip of hardwood was often used, applied over the joint between soundboard and ribs particularly on the treble side. This seems to have been because the extra strings of the baroque lutes had made their pegboxes heavier and longer, thus increasing the pressure between the lute and the supporting knee of the player.

At the lower end, where these ribs taper together, they are reinforced internally with a strip of softwood bent to fit, and externally with a capping strip, usually of the same material as the ribs. At the other end the ribs are glued to a block, often of softwood, to which the neck is attached. In most pictures of medieval lutes up to about 1500, as in the early Arab ‘Ud, the ribs are shown as flowing in a smooth curve into the line of the neck.

Most surviving lutes from the early 16th century have been re-necked in later styles but, from pictures, the early necks appear most often to have been a single piece of hardwood such as sycamore or maple to match the body. {fig 3 Ambassadors] In later and surviving lutes after about 1580 the neck is most often veneered in a decorative hardwood, often ebony, sometimes striped or inlaid with ivory, on a core of sycamore or other common hardwood. At first through the medieval period and into the renaissance, necks were semi-circular or deeper in cross-section. As the number of courses increased through the 16th and 17th centuries, the necks became correspondingly wider, necessitating a change of left-hand position to enable stretches across to the bass strings. This made a thinner neck more comfortable. Baron (1727) commented that Johann Christian Hoffmann (1683 - 1750) made the necks of his lutes to fit the hand of their owner, unlike his father Martin Hoffmann(1653 - 1719) who made his necks too thick.

Separate fingerboards are often not very apparent in pictures of medieval lutes, leading to the supposition that they were either boxwood or simply the flat top surface of the neck. Sometimes when there is a marked change of colour between the “fingerboard” and the soundboard, the join occurs so far down the soundboard it would be beyond any possible neck block and therefore structurally impossible. This must represent a protective coat of something like varnish. Surviving lutes from the 1580’s onward almost universally have separate ebony fingerboards set flush with the soundboard and, after about 1600, usually with separate “points” decorating the joint between fingerboard and soundboard. [fig 1] The lutes of Tielke in the 18th century indeed often had multiple “points.” (see Hellwig, 1980) Medieval and renaissance lute fingerboards were usually flat, even the wide chitarrone and theorbo fingerboards, but from about 1700 makers started to give a curve to their fingerboards, helping the lie of the frets and making fingering easier.

At the back of the top end of the neck a rebate is cut out to form a housing for the pegbox. This same design of joint, with or without a reinforcing nail into the end-grain of the neck, was used throughout the history of the lute, as was the basic form of the pegbox: a straight sided box, closed at the back, open at the front and tapering slightly in both width and depth. However after about 1595 various branches of the lute family also developed different and characteristic pegbox forms in order to accommodate the longer bass strings needed to extend the range of the lute downwards.

Slender tapering hardwood tuning-pegs are inserted from the sides. Medieval pegs appear often to have been made of boxwood but later, in the 17th and 18th centuries, fruitwood such as plum seems to have been a preferred material, though these were often stained black.

There is some controversy about the soundboard material, mainly as a result of confusion about the exact historical distinction between fir, pine and spruce. At all events, it is a flat straight-grained softwood plate, nowadays mostly thought of as Picea abies or Picea excelsa, into which is carved an ornamental rose soundhole, whose pattern often shows decidedly Arabic influence (see Wells, 1981) However it is noticeable that the iconography does not support a continuous tradition of rose design from the Arabic Ud; most medieval pictures of lutes feature gothic designs, and the frequency of Arabic patterns in the later surviving lutes may reflect rather the contemporary interest in such designs by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Dürer. The soundboard is usually made from two halves joined along the centre line, but on larger instruments several pieces may be used. Most surviving lute soundboards are quite thin, often about 1.5mm. However there is some support for the view that the very earliest from c. 1540 may have been rather thicker, and that soundboards were made progressively thinner as the number of the supporting bars was increased. (see Nurse, 1986) Early lutes before the 1590’s usually have no edging to the soundboard. After that, often an ebony or hardwood strip was rebated in to half the depth of the soundboard edge as a protective measure. Later still, when the fashion for re-using old soundboards was in sway (see Lowe, 1976), a ‘lace’ of parchment or cloth with silver threads was often used to wrap the edge, possibly to cover pre-existing wear.

Bridge designs went through a slow evolution, particularly in the shape of the decorative “ears” which terminate both ends, but were consistently made of a light hardwood such as plum, pear or walnut, sometimes stained black, and were glued directly to the surface of the soundboard. Their cross-sectional design was very cleverly arranged to minimise stress at the junction with the thin and flexible soundboard. Holes drilled through the bridge took the strings, which were tied so that they were supported by a loop of the same string rather than by a saddle as in the modern guitar. This has a marked effect on the tone of the instrument, and contributes to the sweetness of the lute’s sound.

The tension of the strings, because they are pulling directly on the soundboard, tends to cause it to distort. This is resisted by a number of transverse bars, of the same wood as the soundboard, glued on edge across its underside. These bars, besides supporting the soundboard, have an important effect on the sound quality. By dividing the soundboard into a number of sections, each with a relatively high resonant frequency, they cause it to reinforce the upper harmonics produced by the string, rather than its fundamental tone. This is matched by the strings themselves, which are quite thin compared with a modern guitar; a thin string tuned to a certain note produces more high harmonics than a thicker string tuned to the same note. Thus the whole acoustical system of the lute is designed to give a characteristically clear, almost nasal, sound.