An Illustrated History of the Lute,

Part 3

It is noteworthy that although all sorts of sizes were available at most times, the general trend from 1600 to 1750 is towards larger instruments for those in common use. Thus for example, we might expect Dowland’s songs to be accompanied on a lute of about 58 cm string length tuned to a nominal g’ or a’, whereas most French baroque music of the mid 17th century calls for an eleven course lute of about 67cm with a top string at a nominal f’, while the lutes used in Germany in the 18th century were mostly 13 course lutes of about 70 - 73cm also with a nominal top string of f’. Some of this may represent a drop in the pitch standard, but we must also assume that string makers had managed to improve their products to increase the total range available, since these size changes represent considerable changes in the instruments’ requirements. Apart from the development of overwound strings which, although invented c.1650, do not seem to have been used for lutes, this increase in range could only have been achieved either by increasing the tensile strength of the trebles, or by increasing the density of bass strings perhaps by the addition of metallic compounds. (see, Peruffo, 1991) There is currently much interest in trying to reproduce these conjectured developments. It is noticeable from written accounts that the cost of strings was remarkably high compared to that of the lutes themselves, leading to the thought that there was more to their manufacture than is now apparent. By the middle of the eighteenth century the variety of this string development was considerable as can be seen in this painting. which shows at least four different types of strings and may imply different added weight-giving compounds.

Although seven course lutes appear as early as the late 15th-century, and Bakfark’s apprentice, Hans Timme, wanted to buy an Italian seven course lute as early as 1556 (see Gombosi, 1967), it was only in the 1580s that they became at all common with the seventh at sometimes a tone, sometimes a 4th, below the sixth. Improved strings are conjectured to have popularised this greater range, perhaps providing a better tone and enabling John Dowland, in his contribution to his son Robert's Varietie of Lute Lessons (1610), to recommend a unison sixth course:

Secondly, set on your Bases, in that place which you call the sixt string, or c ut, these Bases must be both of one bignes, yet it hath beene a generall custome (although not so much used any where as here in England) to set a small and a great string together, but amongst learned Musitians that custome is Ieft, as irregular to the rules of Musicke.

The same book, reflecting the growing tendency to increase the number of bass strings, included English and continental music for lutes with six, seven, eight and nine courses. This only occasionally extended the range to low C; mostly the extra strings were used to eliminate awkward fingerings resulting from having to stop the seventh course. These ‘diapasons’ were usually strung with octaves. Already by 1600 the ten-course lute had made its appearance, shown in contemporary illustrations as constructed like its predecessors, with the strings running over a single nut to the pegbox, which has to be considerably longer to accommodate the additional pegs. The pegbox is also usually shown as being at a much shallower angle to the neck than the earlier renaissance lute, a fact borne out by the surviving original 10 course lute by Christofolo Cocho in Copenhagen (No 96a).

original 10 course lute by Christofolo Cocho in Copenhagen (No 96a) c. 1650.

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

Often the paintings of 10 course lutes show a treble rider, a small extra pegholder on top of the normal pegbox side, designed to keep the top peg clear of the left hand and to give a less acute angle on the nut for the fragile top string.

Another innovation reported by Dowland in Varietie was the lengthening of the neck of the instrument. 'for my selfe was borne but thirty yeeres after Hans Gerles booke was printed, and all the Lutes which I can remember used eight frets ..... some few yeeres after, by the French Nation, the neckes of the Lutes were lengthned, and thereby increased two frets more, so as all those Lutes, which are most received and disired, are of tenne frets'. Initially this may have been done to improve the tone of the low basses, but unless stronger treble strings became available at the same time, the pitch level of these longer lutes must have been lower than the older eight-fret instruments. Interestingly, one such lengthened neck survived until quite recently but when it was ‘restored’ this important evidence of the practice was removed. Sometimes extra wooden frets were glued on to the soundboard, an invention which Dowland attributed to the English player Mathias Mason.

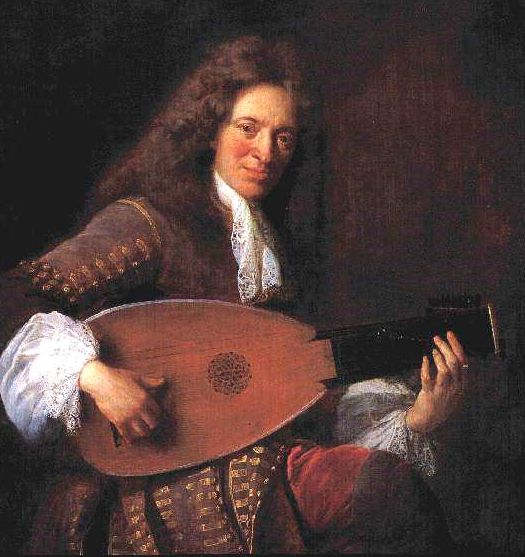

It is interesting that Dowland should thus report the prevailing fashion in lutes as coming from France, for by his death in 1626 France was the dominant culture musically and was the centre for developments in different tunings, starting some time around 1620, which led to the 11 course lute. Lowe (1988) has suggested that the eleventh course may at first have been only an octave string. The later surviving 11 course lutes mostly appear to be conversions from 10 course lutes, all done in the same way, by making the second course single and adding a treble rider for the top string or ‘chanterelle’ on the top of the normal pegbox treble side. This effectively gave two extra pegs which were used for the new bass course, but, because the neck was now too narrow, these strings were taken over an extended nut which projected beyond the the fingerboard and were fastened to the pegs on the outside of the pegbox. The portrait of Charles Mouton, a famous player and composer of the period, clearly shows that this was obviously not regarded as a stopgap measure.

Charles Mouton by François de Troy, Paris, 1690

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

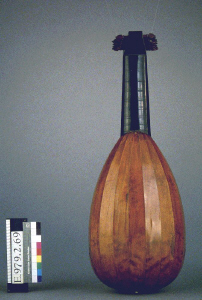

This final extra course on the same string-length has often been attributed to the invention of wirewound or overspun strings, first advertised in England by Playford in 1664. However there is distressingly little hard evidence that these were in fact much used and they are not mentioned by either Mace or the Burwell tutor even though both wrote about the choice of strings, and Mace at some length. As Lowe (1976) has shown, during the 17th century the French were already buying up and converting early 16th century Bologna lutes, seemingly because of a new aesthetic which valued the antique. There are so few surviving lutes with any claim to have been made in France that it is not possible to be sure what their makers were doing by way of new lutes at a time when lute playing was so important to French musical life. The French cannot all have been playing on antique instruments one supposes. Indeed the inventory of the French maker Jean Desmoulins, who died in 1648, points to a vigorous production since it lists 249 lutes in various stages of construction as well as 14 theorbos both large and small (see Lay, 1996). Only one lute from this maker has survived in the Musée de la Musique in Paris, and the face-on view of it shows a remarkable similarity to the lute in the Mouton painting shown above. Alas the all-important soundboard is later, as are the neck, pegbox and bridge. The unusual profile shape of the body though is original and confirms the remark in the Mary Burwell tutor that: “...there is great dispute amongst the Modernes concerning the shape of the lute some will have it somewhat roundish, the rising in the middle of the backe and sloping of each side as wee see the lutes of Monsiour Desmoulins of Paris which are very goode and were sold at first for 20Li and sold still for tenne or twelve. The reason is that the Lute soe framed is capable of more sound because of his Concavity and that the sound not keeping in the deepe and hollow bottome but contrariwise being put forth by the straitnes of the sydes towards the middle and soe to the Rose from whence it issues greater & with more impetuosity. The other have for their defence and reason the handsomness of the figure of the peare the comliness of it because being more flatt in the backe they lye better upon the Stomacke and doe not indanger people to growe crooked. Besides all Bolonia Lutes are in the shape of a peare and those are the best Lutes but there goodness is not attributed to there figure but to there antiquity to the Skill of those Lutemakers to the quality of the woods and seasoning of it and to the varnishing of it. ”

|

|

|

| 11 course lute by Jean Des Moulins, Paris 1644, Musée de la Musique, Paris E. 979.2.69 Photos by Jean-Marc Anglès |

||

Makers working in Italy, where the old tuning held sway, had already addressed the problem of extending the bass range in the 1590’s by the expedient of having longer and therefore naturally deeper-sounding strings carried on a separate pegbox. The theorbo, chitarrone, liuto attiorbato and archlute all had extended straight-sided pegboxes carved from a solid piece of wood set into the neck housing at a very shallow angle and carrying at their ends a separate small pegbox for these extended bass strings. The form of all these instruments is very similar, differing mainly in the length of the extended pegbox, the number of courses carried and whether the bass courses were double or single.

It is commonly said that the chitaronne and theorbo are so large that they require the top one or two strings to be tuned an octave down to prevent them breaking.

This seems on first glance plausible because they are such very large instruments, but, although commonly used as a shorthand description, it is in fact almost the exact opposite of the truth. They are actually not quite big enough, and so the bottom 4 or 5 courses have to be tuned UP an octave. This point is clearly explained by Picinnini in his 1623 account of the origin of the chitarrone but has been largely ignored by most writers except Kevin Mason (in his book The Chitarrone And Its Repertoire in Early Seventeenth-Century Italy, Boethius Press 1989).

The theoretically “correct” size for a lute in low A is about 105-117cm depending on the pitch standard, so, as players start to complain(!) above 87-93cm, theorbos would be seriously underachieving in the bass without this octave transposition upwards. (The top 1 or 2 courses are still slightly below optimum.) The range is therefore diminished by about a seventh, but at the bottom of the range, not the top; thus leading to the need for the extra long basses to restore the range.

It was therefore only to be expected that this principle of longer, and therefore unfingered, bass strings should also be applied to non-continuo lutes. From c.1595 to c.1630 various other types of extended pegboxes were tried for the bass strings. In one version, an extra piece of neck was added on the bass side which carried its own little bent back pegbox. One of these [by Sixtus Rauwolf 1599, though the extension is probably later] has survived in Copenhagen....

Copenhagen, Musikhistorisk Museum (Carl Claudius Samling) No. 93 |

....... and there are several paintings showing this form.

|

|

Although the majority of the paintings of this type seem to be Flemish, it does seem that this form of extended lute was for a time very popular in France as this massed band of lute players in a royal ballet shows.

More widely adopted was a double headed lute with curved pegboxes, one set backwards at an angle rather like the normal lute, the other extended in the same plane as the fingerboard. This carried four separate little nuts to take the bass courses in steps of increasing length.

Hendrik Martensz Sorgh (1611 -1670)

The lute player (detail)

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

This form usually had 12 courses and was apparently invented by Jaques (English) Gaultier c.1630 (see Spenser, 1976; Samson, 1977) but was not used much by the French who stayed largely loyal to their single-headed lutes.

Jacques (English) Gaultier

Engraving by Jan Lievens c. 1630 (Engraving reversed. Gaultier was unlikely to have been left-handed)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

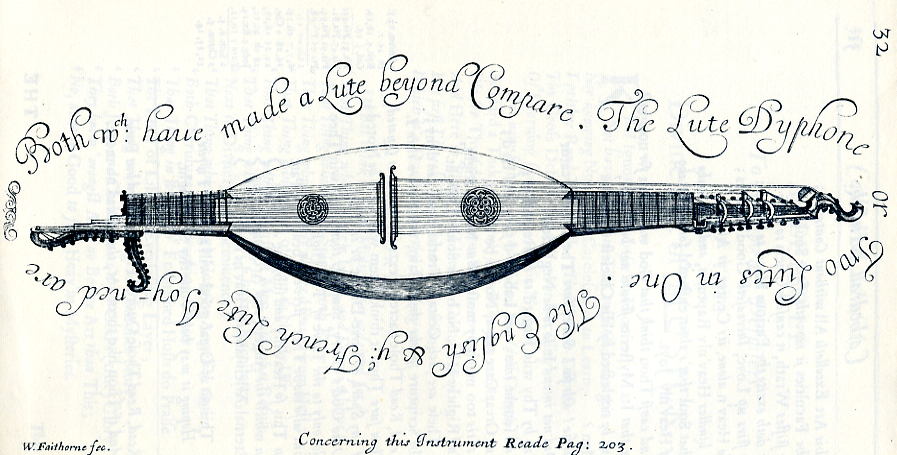

As the author of the Burwell lute tutor (c1670) wrote: 'All England hath accepted that Augmentation and ffraunce att first but soone after that alteration hath beene condemned by all the french Masters who are returned to theire old fashion keeping onely the small Eleaventh'. He, or she, objected to the length of the longer bass strings and felt they rang on too much, thereby causing discords in moving bass lines. It was, however, widely used in England and the Netherlands until at least the end of the 17th century. The apparent thinking behind this form was a desire to avoid the sudden jumps in tone quality between the treble and bass strings which characterise the theorbo and archlute forms. An important tutor for this type of lute, Musick’s Monument, was published by Thomas Mace in 1676, in which he characterises it as a French lute, although Talbot (c1690) in his manuscript called it the 'English two headed lute'. For Talbot the 'French lute' had 11 courses, with all the strings on a single head. There has been some discussion of the usual size for these instruments (see Segerman, 1998) But Talbot measured a 12-course instrument of this type as 59.7cm and the iconography shows all sizes. So far, six examples of this type have turned up with fingered string lengths of between 50 and 75cm.

Thomas Mace, Musick's Monument (London. 1676)

The strange Lute Dyphone which Mace made himself and describes at length in his book, starting, as you can see, on page 203. The left hand side shows the double-headed 12 course lute while the right hand side shows the English theorbo which I discuss next.. . The complete double-ended instrument has recently been reconstructed by Antonio Dattis and is played now by Davide Rebuffa

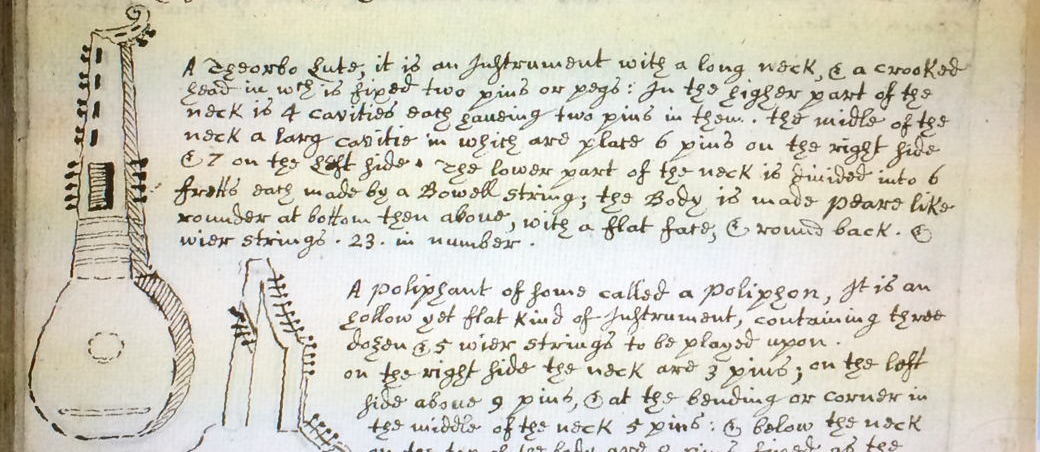

This same principle of stepped nuts for bass strings of gradually increasing length lay behind this specifically English form of the theorbo which was also measured by Talbot (see Sayce, 1995; Edwards, 1995) . Unusually for a theorbo this had double strung courses in the bass which still further smoothed the transition across the range. This is also confirmed by another contemporary rough sketch made by the antiquarian collector of odd facts, Randle Holme, which shows the pairs of pegs for each succeeding bass course down the long theorbo extension.

Randle Holme (1627-1700), The Academie of Armorie 1688. You can see the whole page here.

I am grateful to Davide Rebuffa for alerting me to the existence of this image which I then found in the British Library.

None of these actual instruments has survived and this painting below is one of the few to show this English form of the theorbo in action.

Lady with a Theorbo (c. 1670) by John Michael Wright (1617- 1700)

Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, Ohio, U.S.A.

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

The French too seem to have developed their own version of the theorbo principle in the 17th century with a shorter extension than the Italian theorbo and usually with single stringing. These seem to have been made in two sizes, the smaller for playing solo music and the larger for continuo work. The smaller version “pour les pieces” was measured by Talbot and what seems to be exactly this sort of instrument has survived in Yale. Though now in a form converted to an angelique by the addition of extra pegs in the already long pegbox opening, it is substantially the small French theorbo and fits Talbot’s measurements remarkably closely. Though, sadly, the upper pegbox has been broken, enough remains to confirm the type.

New Haven; Yale Collection of Musical Instruments (Belle Skinner), USA No. 26

Just last year (2013) a large theorbo was reported in Krakow by Piotr Kowaloze and I recognised it as a seemingly genuine French theorbo fitting the description in the Talbot MS. He has written briefly about it in an article for The Lute Vol. 51, 2011. I hope he will write more fully later.

Andreas Berr, 1702

Krakow, Muzeum Narodowe, Nowy Gemach

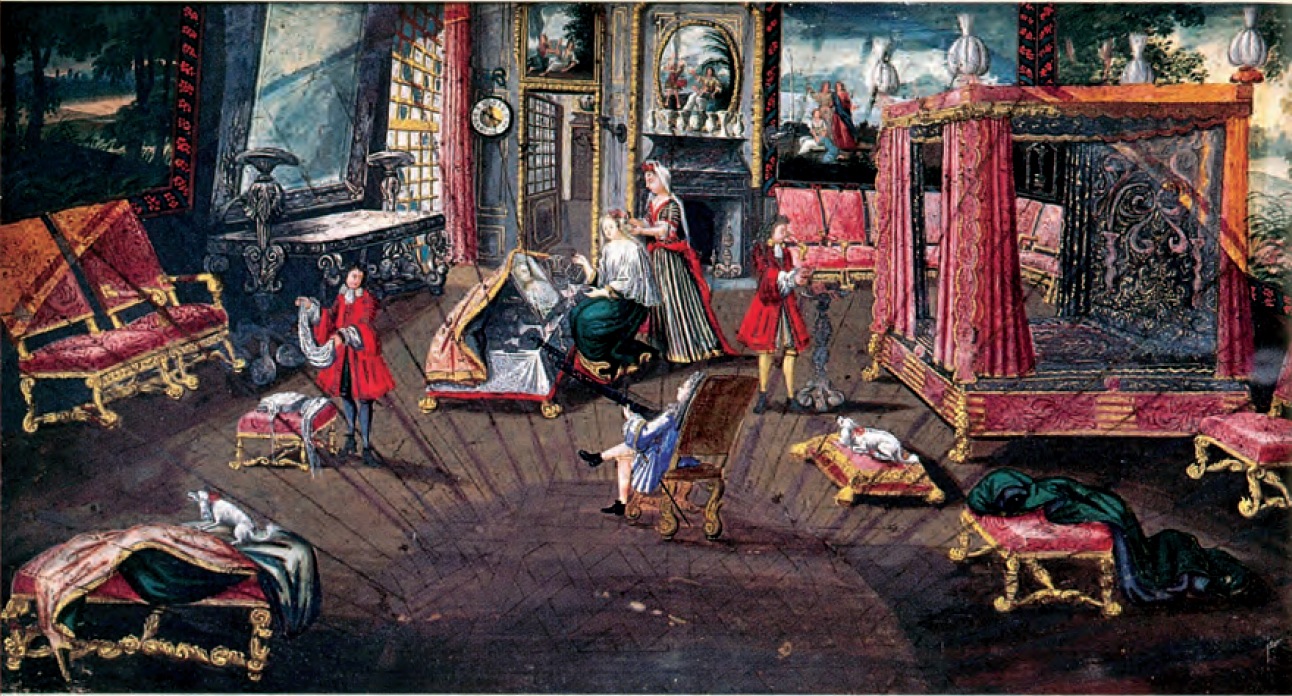

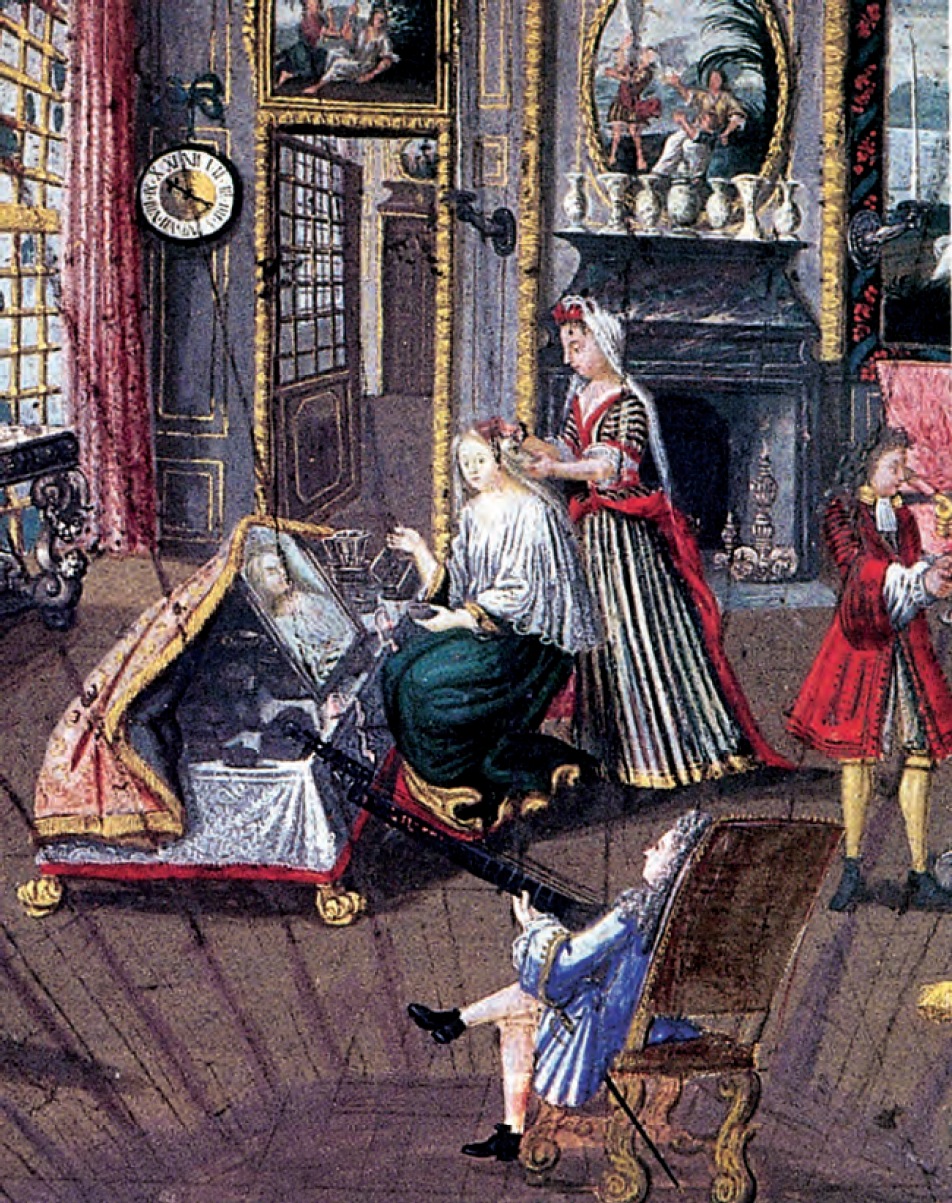

Anon, Franco-Flemish school,

Sold Sotheby’s 29th Oct 2014 Lot 441

A Lute Player, by Antoine Watteau (1684 - 1721) Santa Barbara, Museum of Art

While hardly an accurate portrayal of the instrument this charming fan painting does give an idea of the social position of the best theorbo players in French royal circles.

Anonymous fan painting showing Leonard Ithier, theorbist and viol player to Henrietta-Anne of England, Duchesse d'Orleans [sister of Charles II) playing at his ease in her private chamber while she has her hair done. ( I owe the identification of the theorbo player to Florence Gétreau’s article A rediscovered portrait of Henrietta-Anne of England: music, portraiture, and the arts at the Court of France. Imago Musicae , Libreria Musicale Italia, 2014, XXVI - 2013, pp.7-45.)

Click here to see a reconstruction of the large version of this type of lute.

In Italy in the 17th century the drive towards extending the bass range of the lute was accommodated somewhat more consistently by continuing the theorbo design into smaller lutes for solo use.

1597(?) Lute Player, possibly by Caravaggio(?)

A nice painting of the liuto attiorbato but I have my doubts about the date and whether it’s actually by Caravaggio

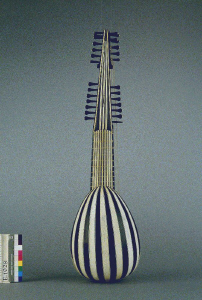

This liuto attiorbato came to be used in addition to normal lutes and theorbos for accompanying singers and continuo work. Matteo Sellas was part of another large German family of instrument makers based in Italy, and produced very elaborate lutes and liuti attiorbati of ivory and ebony at his workshop ‘alla Corona’, at the sign of the crown, in Venice, for instance this fine example currently in the Musée de la Musique in Paris.

|

|

|

Liuto attiorbato by Matteo Sellas, 1638, Musée de la Musique, Paris E. 1028 Photos by Jean-Marc Anglès |

|

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

His brother Giorgio made equally decorative guitars and lutes ‘alla stella’.

Working in Rome, beyond what might seem to be the natural migration range from Germany, were Martinus Harz, David Tecchler, Antonio Giauna and Cinthius Rotundus, from each of whom has survived an archlute, showing this instrument’s importance in Rome in the 17th century. All these Roman archlutes are large (the neck of the Harz has been cut down somewhat) and the surviving Roman repertoire shows them being used as continuo instruments accompanying one of a pair of choirs, the other matching position being taken by a regular theorbo. So clearly they were expected to hold their own in an orchestral setting as much as a theorbo. However the majority of archlutes made in recent years have been based on the much smaller instruments made elswhere in Italy and Germany, these have not proved able to stand up to orchestral forces. In fact they seem only suited to the smaller forces of the Corelli trio sonatas which became so popular throughout Europe. The standard Roman pitch was lower even than the modern idea of low baroque pitch A=415Hz however, and the big Roman archlutes are too big to stand being tuned to modern pitch. This makes for a dilemma when trying to use these large archlutes in a modern performance of its Roman repertoire, The reduction of the neck length in the Harz and the German style extension probably represent the best of this same dilemma appearing in the 18th century. This makes the Harz probably the best instrument to copy for modern conditions. This picture appears to be of such a large Roman archlute and it has a triple rose like the Harz instrument, it is single strung throughout

The Concert, 1615 by Leonello Spada (1576 - 1622) who worked in Rome.

Musée du Louvre

Click here to see a reconstruction of a double strung version of this type of archlute.