An Illustrated History of the Lute,

Part 4

By the beginning of the 18th century, the centre of activity in lute music shifted from France to Germany and Bohemia. The makers extended the range of the instrument still further, and by 1719 composers were writing for 13 courses. There were two types of 13 course lutes developed and it is hard to say which was first, since both are possible conversions from pre-existing 11 course instruments and so labels are not conclusive. Paintings of both types are suprisingly rare. In one version a single pegbox was used like that of the 11 course lute, but, possibly starting as a conversion, a small subsidiary pegbox or ‘bass rider’ with four pegs to take the extra two courses was added to the bass side of the main pegbox.

This had the effect of giving between 5 and 7cm extra length to these two courses. Commonly these lutes were quite large by previous standards with 70 to 75cm being the usual string length.

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

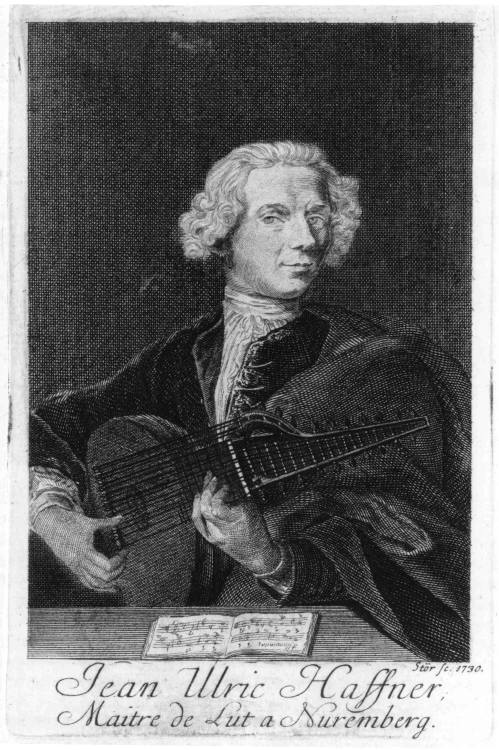

This fine engraving by Stör of the lutenist Ulric Haffner shows the construction of the bass rider pegbox more clearly.

Though the number of strings is obviously somewhat schematic, the offset bridge which implies that this was converted from an 11 course lute is very clear and probably intentional.

A remarkably similar set-up is seen in the lute by Andreas Berr made in Vienna in 1699, presumably as an 11 course and then converted into a 13 course lute by the addition of the bass rider in the early 18th century, with the same result of a heavily offset bridge.

Lute by Andreas Berr, Vienna 1699 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Arthur T. Cabot Fund. 1986.7)

From what has been said so far about stringing this larger string length must imply a lower pitch for the main strings. It is clear from the details of the tablature that Weiss wrote throughout his life for this version of the 13 course lute which was developed by the new wave of German makers, working in Bohemia and Germany itself. Among the most important at this time were Sebastian Schelle and his pupil Leopold Widhalm working in Nürnberg (see Martius, 1996), Martin Hoffmann and his son Johann Christian Hoffmann working in Leipzig, Joachim Tielke and his pupil J. H Goldt working in Hamburg (see Hellwig, 1980) and Thomas Edlinger I of Augsburg and his son Thomas II who moved to Prague and set up his workshop there. All these makers were violin makers as well, reflecting the growing importance of this instrument at a time when the lute was becoming less in demand.

These were also the makers responsible for the other version of the 13 course lute with extended bass strings, the German baroque lute. (see Spencer, 1976) This had an ornately curved double pegbox carved out of a single piece of wood, usually ebonised sycamore. This type did not usually have a treble rider, but did occasionally feature a little separate slot carved in the treble side of the main pegbox to take the top string. Typically this kind of lute had 8 courses on the fingerboard and 5 octaved courses going to the upper pegbox, these five being normally between 25 and 30cm longer than the fingered strings.

Anna Rosina von Lisiewska, a German painter working in Berlin and Dresden

Allegory of Hearing c. 1750

Note the four different coloured strings depicted with such care.

Detail of above painting

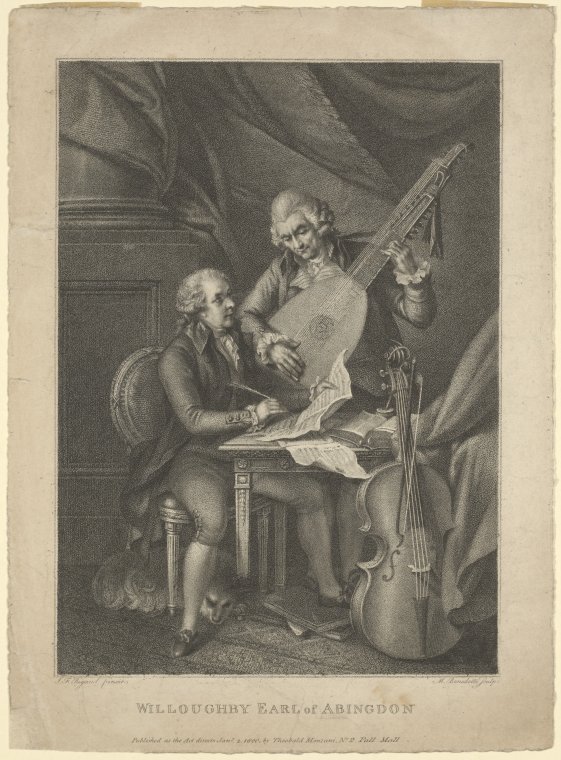

Engraving (after a painting by J F Rigaud) published in London ca. 1800 by Monzani & Co. There are several copies of this print in libraries but this one comes from the New York Public Library showing Willoughby Bertie, Fourth Earl of Abingdon.(seated), and his uncle Mr. Collins playing the lute.

I originally thought the lutenist might possibly be Haydn since the Earl of Abingdon took over organizing the Bach-Abel Concerts in 1782 after the death of Johann Christian Bach and he invited Haydn to London in 1783. However I have since (2019) found out from a very good essay by Derek McCulloch of the Café Mozart ensemble about Willoughby Bertie’s role in musical life that the lutenist is in fact Willoughby Bertie’s uncle Mr. Collins!

You can download Dr. McCulloch’s article from a sidelink on a brief webpage about Willoughby Bertie put together by the Abingdon Area Archaeological and Historical Society. And in it he further remarks that the earl’s first collection of Six Songs and a Duet (published by subscription ca 1788) had a full page copy of Benedetti’s engraving on the inside cover.

Interestingly there is another painting by Zoffany which includes a German baroque lute. It makes one wonder if there was some influence, both Zoffany and Rigaud trained in Rome at the same time and then moved to England and were working in London at the same sort of time, and both were members of the Royal Academy.

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

This design appears to be a modification of the pre-existing angelique form, such as this 1714 Tielke.

In FACTS AND RECOLLECTIONS OF THE XVIIIth CENTURY IN A MEMOIR OF JOHN FRANCIS RIGAUD Esq., R.A.

by his son Stephen Francis Dutilh Rigaud, published in Volume 50 of the Walpole Society 1984, there are two references:

Page 86. In the autumn of this year [1792] my Father received an invitation from the Earl of Abingdon to visit him at his seat at Rycott, where he commenced two portraits of his Lordship, one in a large family picture; the other in which he is represented in the act composing a piece of music; with his Uncle Mr. Collins, trying the effect of it upon the Lute.

Page 94.

My Father exhibited this year [1794] six pictures at the Royal Academy i:e: Whole length portraits of the Earl of Abingdon and Mr. Collins his Uncle in a group; His Lordship is seated at a table in the act of composing music, whilst Mr. Collins, standing near him, is trying the effect of the notes on a Lute

Johann Zoffany (1733 - 1810) The Sharp Family (detail, 1781), oil on canvas 1156mm x 1257mm The National Portrait Gallery,

Angelique by Tielke

Mecklenburgische Landesbibliothek, Schwerin. Note the single stringing of the 16 courses, quite unlike a baroque lute.

Some apparently early 13 course lutes, such as the 1680 Tielke, dating from long before the surviving 13 course music which first appears c.1719, seem to be converted angeliques. Others like the Fux conversion in 1696 of a Tieffenbrucker instrument and the 169? 13 course lute of Martin Hoffmann raise more awkward questions of dating.

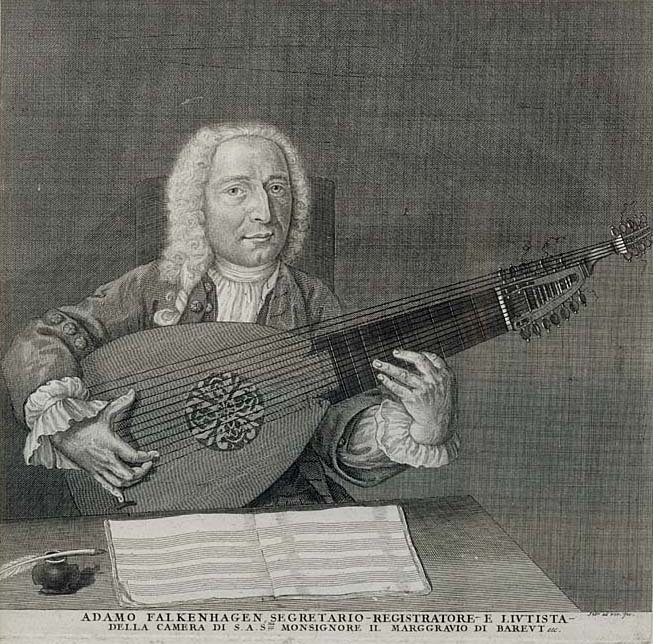

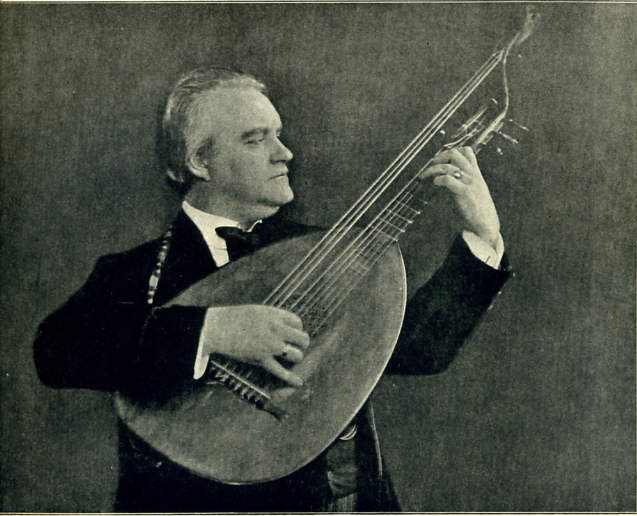

Adam Falkenhagen (1697-c.1765), engraving (c. 1755) from the life by J. W. Stör of Nuremberg. Whatever this instrument actually is, it is clearly a conversion from a lute with fewer courses, as can be seen from the heavily offset bridge.

However he is shown playing a single strung instrument, raising the question whether this is just a graphic simplification or whether Falkenhagen is here playing an angelique, even though the caption describes him as lutenist of the chamber of the Margrave of Bayreuth. This might also be suggested by the form of the lower pegbox which features a little separate slot for the bass two strings as well as the slot for the chanterelle. This bass slot might have been a feature of Tielke’s work as shown in this surviving lute with pegboxes thought to be from an angelique.

Against that, the text below the engraving identifies him specifically as the lutenist of the chamber for the Margrave of Bayreuth.

This whole question of the development of angelique vs. baroque lute is still rather unclear and deserves further research.

(Copenhagen CL104)

An even more elaborate triple pegbox form of this type was also developed and a few examples have survived, notably by Johannes Jauck, a lute and violin maker working in Graz and Martin Bruner [1724 - 1801] in Ollmouc. These seem to have been functionally the same as the double pegbox form, and they may have been another attempt to obtain a smoother transition from treble to bass courses.

Anonymous lute probably made in Italy in 16th century and converted to triple-headed baroque form by Jauck in Graz

Yale, No. 4565.1960 (photo by Kenneth Bé)

Triple-headed baroque lute shown in a chamber music setting on a harpsichord lid of 1765 from Drottningholms teatermuseum

Internally, the barring structure behind the bridge was altered by these makers. Starting with an increase in the number of little treble-side fan bars, finally the characteristic J bar on the bass side of the renaissance lutes was removed and various kinds of fan-barring were introduced right across this area of the soundboard. These seem to have the effect of increasing the bass response. The main transverse bars were also made slightly smaller and more even in height, maybe with the same intention. The body outline of these lutes is remarkably similar to that of the early 16th-century lutes of Frei and Maler and this resemblance may well have been deliberate, for the old instruments continued to be highly prized. It was about this time (1727) that the first systematic history of the lute was written, by E. G. Baron. Referring to the lutes of Laux Maler, he wrote:

But it is a source of wonder that he already built them after the modern fashion, namely with the body long in proportion, flat and broad-ribbed, and which, provided that no fraud has been introduced, and they are original, are esteemed above all others. They are highly valued because they are rare and have a splendid tone.

This echoes the value put on Maler lutes in the Fugger inventory of nearly 200 years earlier, which talks of ‘An old good lute by Laux Maler’ and ‘One old good lute by Sig[ismond] Maler’. Baron’s comment on the possibility of fraud is also interesting in this context, since there are several surviving lutes with supposedly 16th century Tieffenbrucker labels which are clearly the work of Thomas Edlinger working in Prague at about the time Baron was published. Thomas Mace too, writing of Maler, says, ‘..but the Chief Name we most esteem, is Laux Maller, ever written with Text Letters: Two of which Lutes I have seen (pittiful Old, Battered, Crack’d Things) valued at 100l. a piece.’

In the 18th-century a much simpler form of German ‘lute’, the mandora, emerged with the same string lengths and barring system as the baroque lute but usually with only six or eight courses in a variety of tunings, one of which was identical to the modern guitar tuning. Apparently mainly used by amateurs, it also found a useful niche in orchestras in place of the 13 course baroque lute.

Peter Jakob Horemans, Porträt eines Hofmusikers, (Detail)

(The musician, not shown here, wears the livery of the Bavarian court trumpet band and is surrounded by all the instruments of the orchestra, including this mandora).

Munich, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Mu 280

Click here to see a reconstruction of this type of lute.

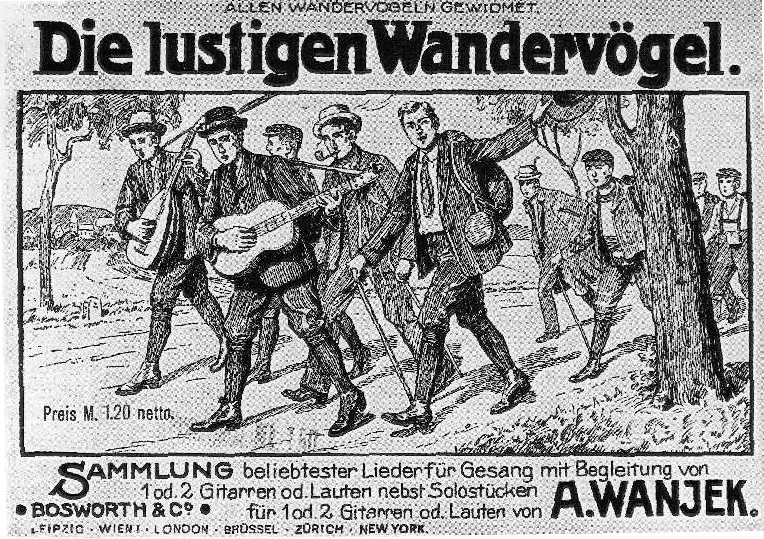

As a kind of postscript to the history of the lute proper, this late mandora form seems to have mutated in the late 19th and 20th centuries into a guitar in lute shape, with the six single strings of a guitar and with guitar tuning. Large numbers of these were made in Germany from the beginning of the 20th century until just after 1945 and they still turn up on the secondhand market as lutes. They were well but very heavily made, usually with separate carved roses of pearwood, fixed metal frets and often have guitar style machine heads instead of pegs, sometimes in curved crook-style pegboxes or sometimes on flat guitar-type pegheads. Now known as lute-guitars or Wandervögel lutes, they were very popular especially in Germany and were used for accompanying folk songs and formed part of late 19th century Romantic German idealism which found expression in the Wandervögel walking club movement.

“Die Lustigen Wandervögel”

Picture kindly supplied by Thomas Schall, who has a short history of the Wandervögel lute (in German) here

And here is a girls version from 1913!

They sometimes were even made with extended bass strings in some faint echo of the original German baroque lute form, perhaps influenced by the so-called “Swedish theorbo”.

Hans Schmid-Kayser, Schule des Lautenspiels als Begleitung zum Gesang.

Published, Berlin 1914

Throughout the lute’s history, apart from these late lute-guitars, the gut strings have been matched by moveable gut frets tied round the neck. The placing of these frets has always been a problem to both theoreticians and players, and many attempts have been made to find a system that will give the nearest approach to true intonation on as wide a range of intervals and in as many positions as possible. A number of writers, including Gerle (1532), Bermudo (1555), the anonymous author of Discours non plus mélancholique (1557), Vincenzo Galilei (Il Fronimo, 1568) and John Dowland put forward various systems, many of which were based on Pythagorean intervals. Late I6th-century theorists in Italy, as well as 17th-century writers such as Praetorius and Mersenne, habitually assumed that the intonation of the lute (and other fretted instruments) represented equal temperament, whereas keyboard instruments were tuned to some form of mean-tone temperament.

Günther Hellwig: Joachim Tielke, Ein Hamburger Lauten- und Violenmacher der Barockzeit, (Frankfurt am Main ,1980)

Klaus Martius: Leopold Widhalm, und der Nürnberger Lauten- und Geigenbau im 18. Jahrhundert, (Frankfurt am Main, 1996)

Sandro Pasquale & Roberto Regazzi:Le Radici del successo della liuteria a Bologna, (Bologna, 1998)

Ray Nurse: ‘Design and Structural Development of the Lute in the Renaissance’, Proceedings of the International Lute Symposium, (Utrecht, 1988)

Kevin Coates: Geometry, Proportion and the Art of Lutherie, (Oxford, 1985)

Monika Burzik:Quellenstudien zu europäischen Zupfinstrumentenformen, (Kassel 1995)

A. L. Lloyd: ‘The Rumanian Cobza’, LSJ. ii (1960), 13

Edmund A. Bowles: Musical Performance in the Late Middle Ages, (Minkoff, 1983)

Peter Kiraly: ‘Some new facts about Vendelio Venere’ LSJ. xxxiv (1994), 26 and LSJ. xxxv (1995), 73

Peter Forrester: ‘An Elizabethan Allegory and some hypotheses’ LSJ. xxxiv (1994), 11

John Downing: ‘The Maler and Frei Lutes - Some Observations’ FoMRHI Bull. 11 (1978), 60

Mimmo Peruffo: ‘New hypothesis on the construction of bass strings for lutes and other gut-strung instruments’ FoMRHI Bull. 62 (1991), 22

Keith Polk: German Instrumental music of the Late Middle Ages, (Cambridge 1992)

E. Segerman: ‘The size of the English 12-course lute’ FoMRHI Bull. 92 (1998), 31

Lynda Sayce: ‘Continuo lutes in 17th and 18th-century England’ Early Music xxiii/4 (November 1995), 666

Lynda Sayce: ‘Performing Purcell; A question Answered?’ Early Music Review (March 1995),

D. Edwards: ‘Talbot’s English theorbo reconsidered’ FoMRHI quarterly, Bull. 78, (1995), 32

Stefano Toffolo: Antichi Strumenti Veneziani, 1500-1800: Quattro Secoli di Liuteria e Cembalaria. (Venice, 1987)

Peter Päffgen: Laute und Lautenspiel in der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts (Regensburg, 1978)

Peter Lay: ‘French Music for solo theorbo - an introduction’ Lute News, No. 40, (1996), 3

Catherine Massip: ‘Facteurs d’instrument et maîtres à danser parisiens au XVIIe siècle’ Instrumentistes et Luthiers Parisiens XVII - XIX siècles, (Paris, no date)

Catherine Massip: La vie de musiciens de Paris au temps de Mazarin (Paris, 1976)

Elisabeth Wells:‘An Early stringed keyboard instrument’ Early Music Vol 6 No.4 (October 1978), 568

Sandro Pasqual: ‘Laux Maler (c.1485 - 1552)’ Lute News, No.51 (1999), 5 - 15

M.G.Lowe: ‘Renaissance and Baroque Lutes: A false dichotomy. Observationes on the lute in the seventeenth century’. Proceedings of the International Lute Symposium, Utrecht, 1988

Joel Dugot & others: Luths et luthistes en Occident(Paris, 1999)